An Open-Label, Single-Arm, Non-Randomized, Prospective, Observational Multi-Center PMS Study to Assess the Efficacy and Safety of Cilnidipine in the Management of Essential Hypertension in a Franco-African Population.

Une étude ouverte, à un seul bras, non randomisée, prospective, observationnelle et multicentrique, pour évaluer l'efficacité et l'innocuité de la cilnidipine, dans la prise en charge de l'hypertension essentielle dans une population franco-africaine

S COULIBALY¹, N YVES², S KUMAR³, I DESAI MISTRY⁴.

RESUME

Introduction : L’hypertension artérielle (TA) ou hypertension est une préoccupation mondiale, touchant particulièrement le continent africain. Malgré les traitements disponibles, l'hypertension persiste chez de nombreux patients. La cilnidipine, un inhibiteur calcique de nouvelle génération (CCB), offre des avantages potentiels et a démontré son efficacité et sa sécurité dans le traitement de l'hypertension. Cette étude vise à évaluer l'efficacité antihypertensive et l'innocuité de la cilnidipine chez les patients de l'hôpital Point G (Mali) et de l'hôpital universitaire de Treichville (Côte d'Ivoire).

Méthodes : Une étude observationnelle prospective multicentrique a été menée de juin 2022 à mai 2023 en Côte d’Ivoire et au Mali pour évaluer l’efficacité et l’innocuité de la cilnidipine dans la prise en charge de l’hypertension artérielle essentielle. Soixante-trois personnes nouvellement diagnostiquées souffrant d’hypertension, âgées de 18 à 65 ans, ont été incluses dans l’étude. Les objectifs principaux comprenaient l’évaluation de l’efficacité par la variation moyenne de la pression artérielle systolique (TAS), de la pression artérielle diastolique (TAD) et de la fréquence cardiaque (FC) entre le départ et 12 semaines. La cilnidipine a été administrée par voie orale (5 ou 10 mg) selon les caractéristiques du patient et le jugement du médecin traitant. Les événements indésirables ont été surveillés. L’analyse statistique comprenait des mesures répétées de l’ANOVA et a été ajustée pour tenir compte de comparaisons multiples à l’aide de la correction de Bonferroni (p < 0,05).

Résultats : Dans cette étude impliquant 76.2 % de femmes (N= 48) et 23.8 % d’hommes (N= 15), le traitement à la cilnidipine a démontré des réductions significatives de la pression artérielle systolique (PAS), de la pression artérielle diastolique (PAD) et de la fréquence cardiaque sur 12 semaines. La PAS moyenne des patients a diminué de 166.84 mmHg au départ à 126.63 mmHg à la semaine 12 (p < 0.05), tandis que leur PAD moyenne a diminué de 88.81 mmHg à 73.32 mmHg (p < 0.05). La fréquence cardiaque a diminué de 83.31 bpm à 70.93 bpm (p < 0.05). Les événements indésirables étaient légers, avec des étourdissements, des maux de tête, des vomissements et des bouffées vasomotrices signalés par (14.29 %), des patients. Aucun œdème périphérique ou éruption cutanée n'ont été observés.

Conclusion : La cilnidipine réduit efficacement la PAS, la PAD et la FC chez les patients hypertendus avec des effets indésirables minimes, comme observé dans les hôpitaux du Mali et de Côte d'Ivoire. Son profil d’innocuité favorable suggère qu’il s’agit d’une bonne option thérapeutique pour les patients hypertendus. Cependant, des limites telles qu'une petite taille d'échantillon, un suivi court, l'absence de groupe témoin et un biais de sélection potentiel doivent être prises en compte. Des essais contrôlés randomisés plus vastes sont nécessaires pour confirmer son efficacité et sa sécurité dans la gestion de l'hypertension.

Mots-clés

Cilnidipine, Hypertension artérielle, contrôle tensionnel, innocuité.

SUMMARY

Introduction: High blood pressure (BP) or hypertension is a global concern, particularly affecting the African continent. Despite available treatments, hypertension persists in many patients. Cilnidipine, a new-generation calcium channel blocker (CCB), offers potential benefits and has demonstrated efficacy and safety in the treatment of hypertension. This study aimed to evaluate the antihypertensive efficacy and safety of cilnidipine in patients at Point G Hospital (Mali) and Treichville University Hospital (Côte d'Ivoire).

Methods: A prospective, multicenter observational study was conducted from June 2022 to May 2023 in Côte d'Ivoire and Mali to evaluate the efficacy and safety of cilnidipine in the management of essential hypertension. Sixty-three newly diagnosed individuals with hypertension, aged 18 to 65 years, were included in the study. The primary objectives included assessing efficacy by the mean change in systolic blood pressure (SBP), diastolic blood pressure (DBP), and heart rate (HR) from baseline to 12 weeks. Cilnidipine was administered orally (5 or 10 mg) according to patient characteristics and the judgment of the treating physician. Adverse events were monitored. Statistical analysis included repeated measures ANOVA and was adjusted for multiple comparisons using the Bonferroni correction (p < 0.05).

Results: In this study involving 76.2% women (N=48) and 23.8% men (N=15), cilnidipine treatment demonstrated significant reductions in systolic blood pressure (SBP), diastolic blood pressure (DBP), and heart rate over 12 weeks. Patients' mean SBP decreased from 166.84 mmHg at baseline to 126.63 mmHg at week 12 (p <0.05), while their mean DBP decreased from 88.81 mmHg to 73.32 mmHg (p <0.05). Heart rate decreased from 83.31 bpm to 70.93 bpm (p <0.05). Adverse events were mild, with dizziness, headache, vomiting, and flushing reported by 14.29% of patients. No peripheral edema or rash was observed.

Conclusion: Cilnidipine effectively reduces SBP, DBP, and HR in hypertensive patients with minimal adverse effects, as observed in hospitals in Mali and Côte d'Ivoire. Its favorable safety profile suggests that it is a good therapeutic option for hypertensive patients. However, limitations such as a small sample size, short follow-up, lack of a control group, and potential selection bias should be considered. Larger randomized controlled trials are needed to confirm its efficacy and safety in the management of hypertension.

KEY WORDS

Cilnidipine, Hypertension, Blood Pressure Control, Safety.

1. F M P O S [Faculte De Medecine, De Pharmacie Et Odonto Stomatologie, Médecin Chef Polyclinique des Armées, Kati, Bamako, Chef de service de Cardiologie CHU Point G, Bamako, Mali.

2. Institut De Cardiologie D’abidjan, Hospital Center University De Treichville, 7XVV+5P4, Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire.

3. Dr. Shalini Kumar, Associate Vice President, Medical Services Intl Business, Ajanta Pharma, Mumbai, Maharashtra, India.

Ms. Isha Desai Mistry, Assistant General Manager Marketing, Intl Business, Ajanta Pharma, Mumbai, Maharashtra, India.

Adresse pour correspondence

Ajanta Pharma, Satellite Gazebo, 167 Guru Hargovindji Marg, Chakala, Andheri (E), Mumbai, 400099, B Wing, 301/302, 3rd, Andheri Ghatkopar Link Road-Extension, Chakala, Andheri East, Mumbai, Maharashtra 400093.

Email : This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

INTRODUCTION

Hypertension, defined as persistently elevated blood pressure (BP) (≥140/90 mmHg), is a prevalent chronic medical condition. It is a significant contributor to cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) and mortality rates globally, particularly impacting low- and middle-income countries. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that worldwide, approximately 1.28 billion adults aged 30 to 79 years are affected by hypertension. The WHO African Region has the highest prevalence of hypertension, at 27%.

Antihypertensive therapy aims to decrease cardiovascular morbidity and mortality associated with hypertension by lowering it and addressing other cardiovascular risk factors. In a study examining hypertension management in sub-Saharan Africa, it was found that 40% of patients had uncontrolled hypertension despite receiving antihypertensive medication. Consequently, there is a need to reassess treatment approaches, which may involve lifestyle modifications, adjustments to antihypertensive drugs or dosages, and exploration of newer-generation drugs.

Calcium channel blockers (CCBs) are among the most commonly prescribed antihypertensive medications due to their efficacy in lowering BP, favorable tolerability, and ability to reduce cardiovascular and renal complications associated with hypertension. Notably, CCBs have been identified as one of the most effective drug classes for reducing BPin people of African descent.

Dihydropyridine CCBs primarily induce vasodilation and are preferred in cases of advanced age, isolated systolic hypertension, peripheral vascular disease, carotid atherosclerosis, angina pectoris, and even pregnancy. However, some, like amlodipine, are associated with pedal edema, an adverse effect also observed with felodipine, nisoldipine, and nicardipine. Cilnidipine, a new-generation dihydropyridine CCB, has shown a significant reduction in pedal edema occurrence compared to amlodipine (p<0.05).

Cilnidipine, a dual channel blocker (L- and N-type calcium channel-blocking activity), has exhibited renoprotective, neuroprotective, and cardioprotective effects in many clinical and preclinical studies. Beyond its calcium channel-blocking actions, cilnidipine shows pleiotropic effects, potentially beneficial in CVD treatment. Clinical evidence also supports its efficacy in reducing BP, especially in morning and white-coat hypertension, with minimal central nervous system adverse effects. Further, meta-analyses affirm its safety and efficacy in managing mild-to-moderate essential hypertension.

Given its potential as a promising therapeutic option for comprehensive cardiovascular management in hypertension, we conducted this study to assess the antihypertensive efficacy and safety of cilnidipine in Point G Hospital (Mali) and CHU Treichville (Cote d’Ivoire).

METHODS

An open-label, single-arm, non-randomized, prospective, observational multicenter post-marketing surveillance study was conducted from 01/06/2022 to 01/05/2023 to assess the efficacy and safety of cilnidipine in managing essential hypertension within the patients of Hospital Point G (Mali) and at the Treichville University Hospital (Côte d'Ivoire). This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University Hospital Center of Treichville in Abidjan, Côte d'Ivoire.

The study was conducted across two hospitals in Côte d'Ivoire and Mali, both of which are located in urban areas within sub-Saharan Africa. Sixty-three newly diagnosed hypertensive patients, aged 18 to 65 years, were enrolled by physicians after an initial screening that considered demographic data, medical history, family history, and clinical examination. Before participation, written informed consent was obtained from every patient. The primary objective of the study was to assess the effectiveness of cilnidipine, specifically focusing on the change in systolic BP (SBP), diastolic BP (DBP), and heart rate (HR) from baseline to 12 weeks post-treatment. Additionally, the study monitored adverse events to evaluate the safety of cilnidipine.

Tables 1 and 2 present the inclusion and exclusion criteria for the study, respectively. To be eligible for participation in the study, patients were required to meet all specified criteria for study participation. Additionally, patients were not included in the study if any of the exclusion criteria were present.

Table 1: Inclusion Criteria for the Study

|

S. No |

Inclusion Criteria |

|

Criteria 1 |

Age 18-65 years |

|

Criteria 2 |

Patients with newly diagnosed hypertension (BP ≥ 140/90) |

|

Criteria 3 |

Patients with hypertension without co-morbid conditions |

|

Criteria 4 |

Willing to provide informed consent |

BP: blood pressure

Table 2: Exclusion Criteria for the Study

|

S. No |

Exclusion Criteria |

|

Criteria 1 |

Age < 18 or > 65 years |

|

Criteria 2 |

Hypertension with co-morbid conditions |

|

Criteria 3 |

SBP ≥ 180 mmHg and/or DBP ≥ 110 mmHg |

|

Criteria 4 |

Current use of medications that are known to be potent inhibitors or inducers of CYP3A4 and in part by CYP2C19. Care is to be taken if the patient is on these medicines (digoxin, cimetidine, rifampicin, azole antifungal agents, itraconazole, miconazole, etc.) or is taking grapefruit juice. |

|

Criteria 5 |

Pregnancy, lactation, or lack of contraception use in women of childbearing potential |

|

Criteria 6 |

Patients with preexisting edema, headache/migraine, cor pulmonale, nephrotic syndrome, hypoproteinemia, or anemia who are on drugs such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and amantadine |

|

Criteria 7 |

Any other clinical condition, contraindication, or drug interaction that is deemed unsafe by the physician |

CYP3A4: enzyme cytochrome P450 3A4; CYP2C19: enzyme cytochrome P450 2C19; SBP: systolic blood pressure; DBP: diastolic blood pressure

Table 3 outlines the recorded reasons for subject withdrawal. However, it is important to emphasize that while the provided terms for withdrawal are included in this list, the list is not exhaustive. Reasons for premature discontinuation were documented in all cases.

Table 3: Discontinuation/withdrawal criteria for the study

|

S. No |

Discontinuation/Withdrawal Criteria |

|

Criteria 1 |

Withdrawal of consent |

|

Criteria 2 |

Serious or intolerable adverse event |

|

Criteria 3 |

Poor BP control |

|

Criteria 4 |

Poor treatment compliance |

BP: blood pressure

A total of 63 patients met the inclusion criteria and were selected for the study. The patients were followed for 3 months and assessed at 4-, 8-, and 12-week intervals. The following actions were carried out subsequently:

- • After initial screening, the patient's demographic data (gender, age, weight, height, body temperature, pulse rate, and respiratory rate) and medical history (concurrent diseases, duration, drug, dosage, and treatment duration) were recorded at baseline. BP, HR, pedal edema, and adverse events were recorded in the case report form (CRF) at each visit.

- • Cilnidipine tablets of 5 or 10 mg were prescribed by medical personnel and self-administered orally every day after breakfast. The dose was based on the patient's BP and was determined by the physician’s clinical judgment. Both the physician and patient were informed of the dose administered.

- • BP and HR were measured at baseline and 4, 8, and 12 weeks and recorded as SBP, DBP, and HR in the CRF. BP was measured using the OMRON BP machine.

- • Pedal edema was clinically assessed over the medial malleolus of both legs during enrollment and at each subsequent visit. The presence of pedal edema on either leg was regarded as a side effect.

- • Any additional adverse events, including headaches, that occurred during the study were documented in the follow-up appointments.

The statistical methods employed in this study included a variety of analyses to evaluate several aspects of the data collected. Repeated measures ANOVA was performed to analyze the changes in SBP, DBP, and HR from baseline to week 12 (including at weeks 4 and 8) for patients on cilnidipine 5 mg versus 10 mg. Analyses were adjusted for multiple comparisons using the Bonferroni correction. No imputation was made for missing data; it was treated as missing. A significance level of 0.05 was set, and a p-value less than 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

Patient Disposition

The study included 63 patients with newly diagnosed hypertension. Among them, 48 (76.2%) were female and 15 (23.8%) were male. Table 4 summarizes the baseline patient characteristics, including age, weight, height, temperature, pulse rate, and respiratory rate for the study population.

Table 4: Baseline Patient Characteristics

|

Characteristic |

Minimum |

Maximum |

Mean |

|

Age (years) |

18 |

65 |

51 |

|

Weight (kg) |

54 |

98 |

73 |

|

Height (cm) |

153 |

185 |

168 |

|

Temperature (°C) |

35 |

38.5 |

37 |

|

Pulse (bpm) |

66 |

112 |

83 |

|

Respiratory rate (BPM) |

15 |

22 |

18 |

Treatment Allocation

The distribution of patients receiving cilnidipine 5 mg (24 patients) and cilnidipine 10 mg (39 patients) was determined by the treating physician, considering individual patient characteristics such as age, gender, baseline BP levels, and comorbidities.

During the study, the number of patients attending follow-up visits decreased with each appointment, with a total of 55 patients consistently following up till the study endpoint. The follow-up rate in our study is likely impacted by the common issue of patient attrition over time, which is observed in many long-term studies. As the study progressed, various factors such as health concerns, financial constraints, and logistical challenges may have contributed to the dropout of 8 patients (12,6%). While regular reminders, flexible follow-up options, and patient engagement initiatives were implemented to improve retention, patients who dropped out were not included in the final analysis to maintain consistency.

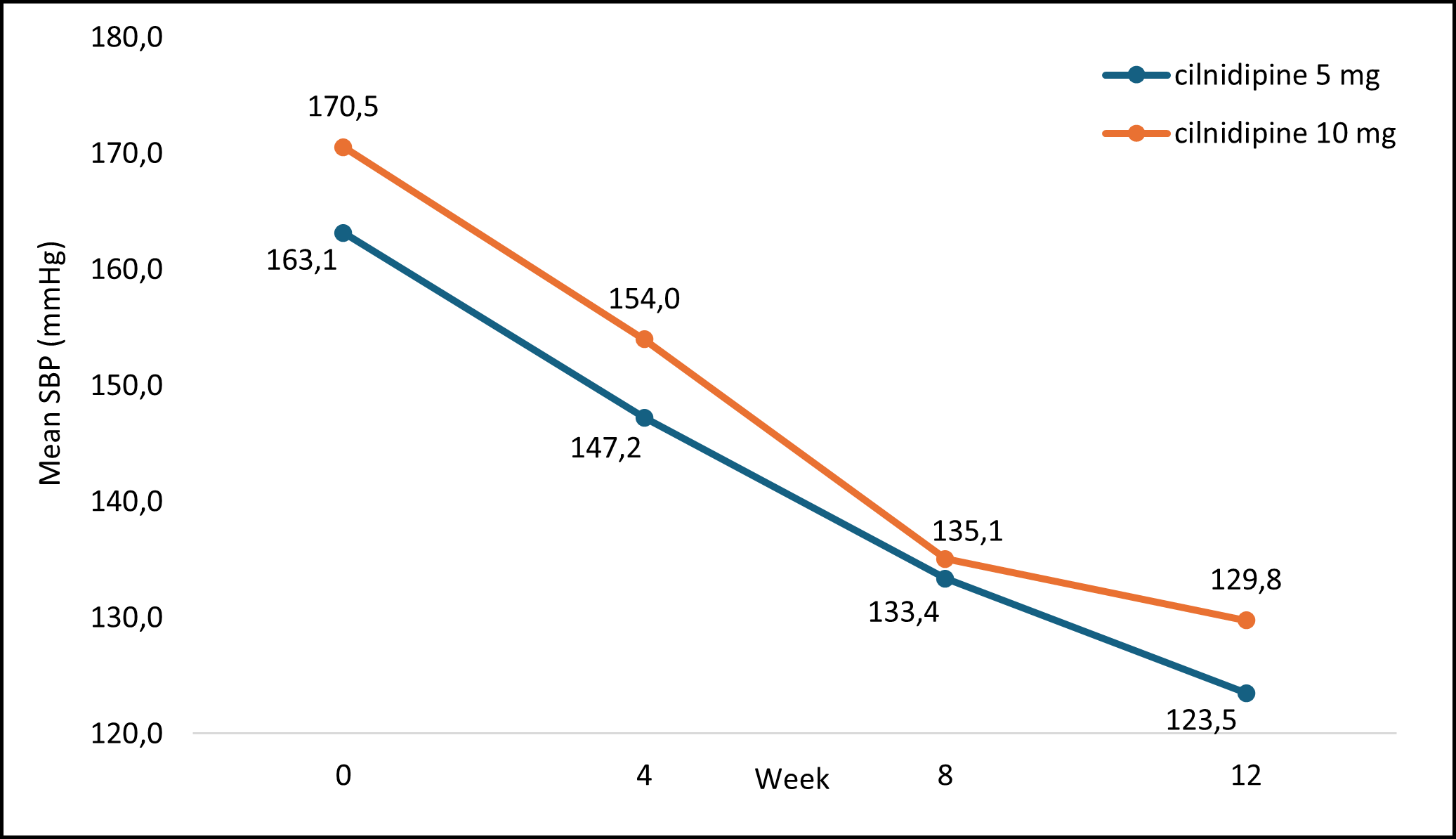

SBP Values

The patient data of SBP changes were analyzed at each visit to evaluate the correlation with cilnidipine treatment. The analysis revealed a significant direct correlation between SBP and cilnidipine treatment at each visit at 4 (p=<0.05), 8 (p=<0.05), and 12 weeks (p=<0.05).

The mean changes in SBP are showcased in Table 5, illustrating the alterations in SBP measurements among the study participants over the 12-week duration.

Table 5 : Mean SBP Measurement of Study Participants at Each Visit From Baseline to Week 12

|

SBP |

Patients |

Mean (mmHg) |

SE |

P value |

|

Baseline |

63 |

166.84 |

2.42 |

NA |

|

Week 4 |

60 |

150.60 |

2.01 |

<0.05 |

|

Week 8 |

57 |

134.22 |

3.41 |

<0.05 |

|

Week 12 |

55 |

126.63 |

1.65 |

<0.05 |

Figure 1 illustrates the mean SBP measurements at each visit after treatment with cilnidipine. Based on the data, it is evident that the average mean SBP values significantly reduced over the 12 weeks.

SBP: systolic blood pressure; mmHg: millimeters of mercury

Figure 1: Mean SBP Measurement at Each Visit With cilnidipine Treatment

DBP Values

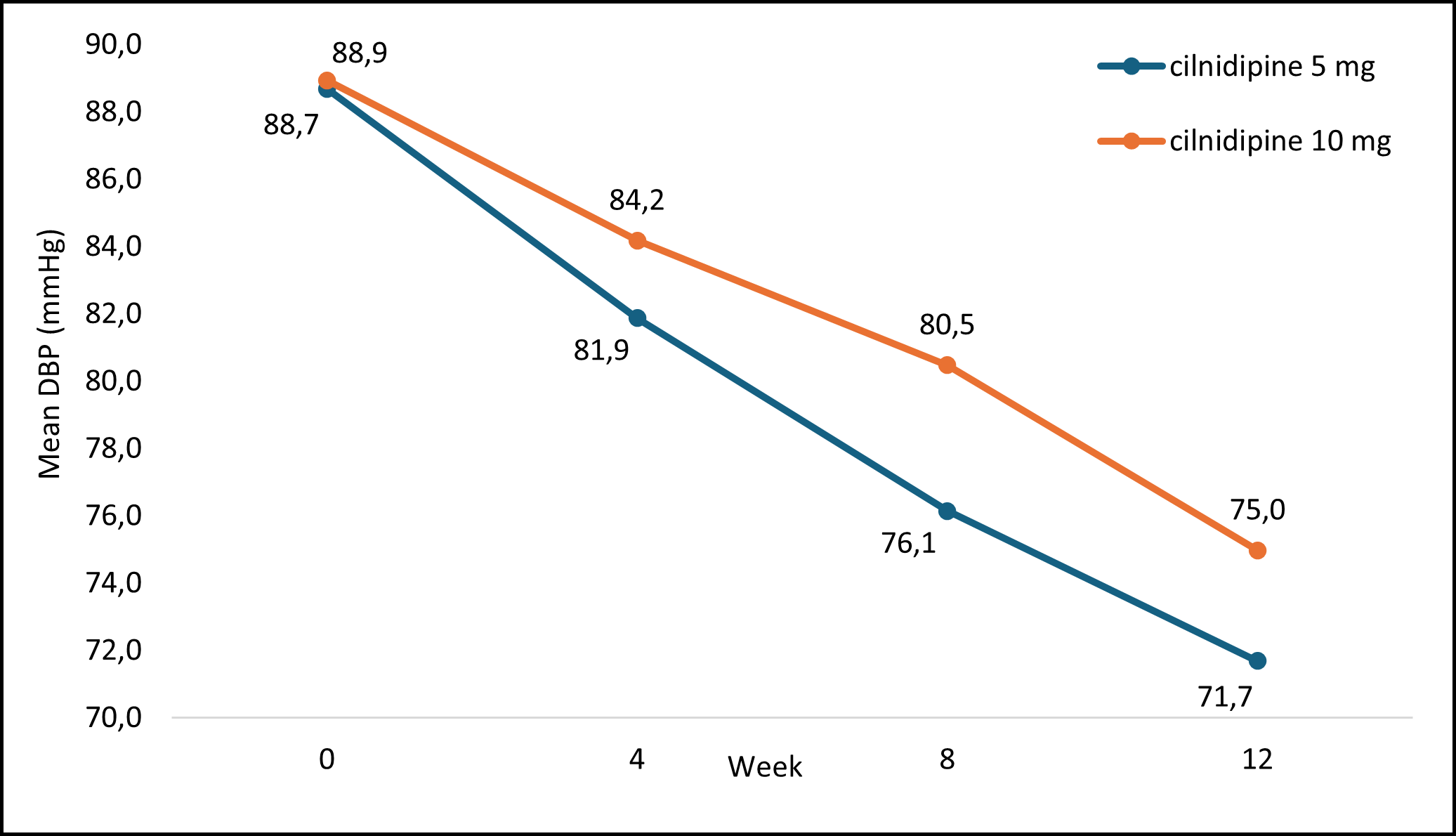

The analysis of DBP changes in patients at each visit was conducted to assess the correlation with cilnidipine treatment. The results revealed a significant direct correlation between DBP and cilnidipine treatment at each visit: 4 weeks (p=<0.05), 8 weeks (p=<0.05), and 12 weeks (p=<0.05).

The mean changes in DBP are presented in Table 6, demonstrating the variations in DBP measurements among the study participants over the 12-week duration.

Table 6 : Mean DBP measurement of study participants at each visit from baseline to week 12

|

DBP |

Patients |

Mean (mmHg) |

SE |

P value |

|

Baseline |

63 |

88.81 |

2.3 |

NA |

|

Week 4 |

60 |

83.02 |

1.44 |

<0.05 |

|

Week 8 |

57 |

78.30 |

1.49 |

<0.05 |

|

Week 12 |

55 |

73.32 |

1.26 |

<0.05 |

DBP: diastolic blood pressure; mmHg: millimeters of mercury; SE: standard error, NA: not applicable

Figure 2 highlights the mean DBP values recorded at every visit with cilnidipine treatment. The average mean DBP values significantly decreased over 12 weeks.

DBP: diastolic blood pressure; mmHg: millimeters of mercury

Figure 2: Mean DBP Measurement at Each Visit with Cilnidipine Treatment

HR Values

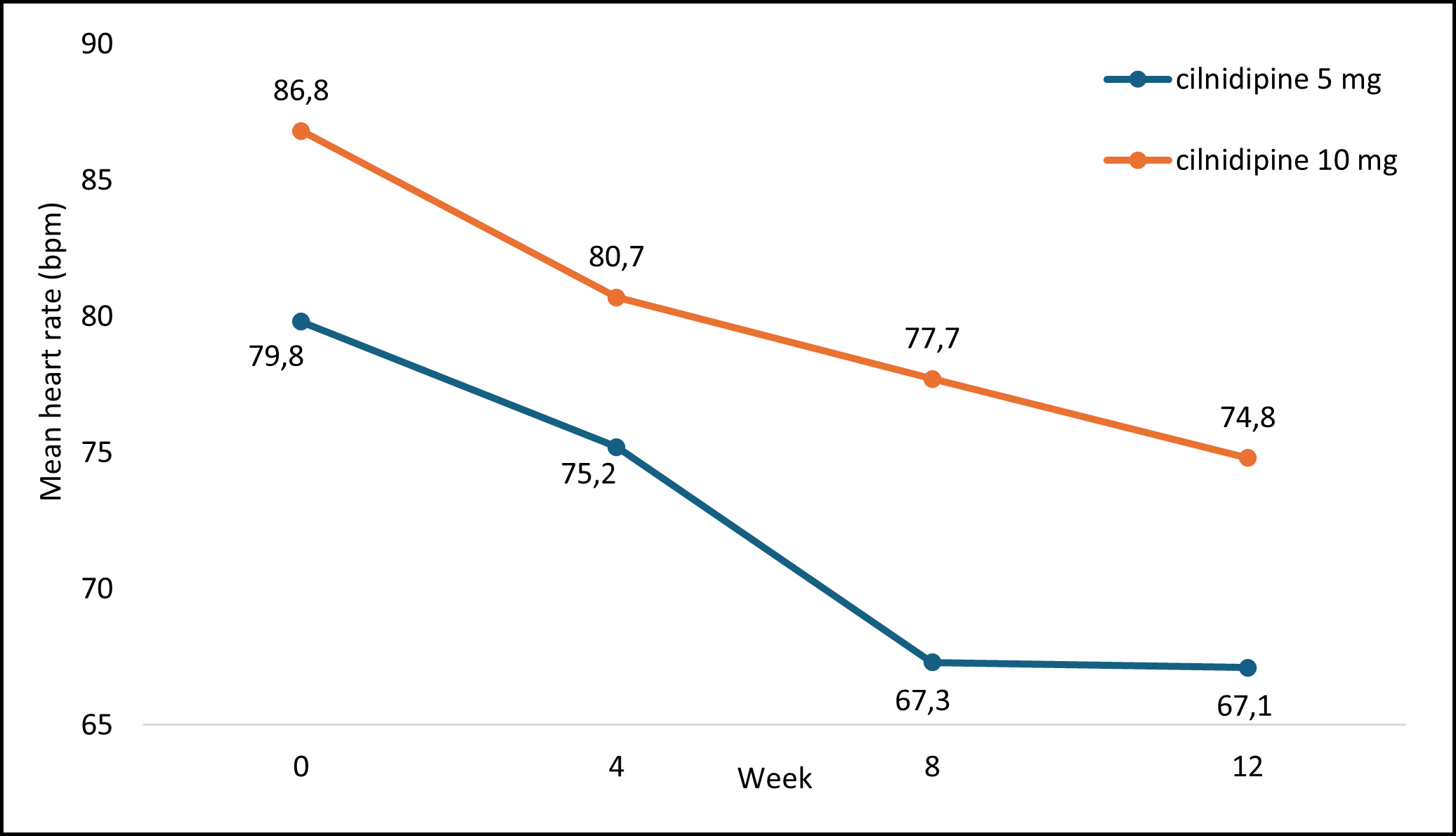

The analysis of changes in the HR of patients at each visit aimed to evaluate the correlation with cilnidipine treatment. The findings indicated a direct significant correlation between HR and cilnidipine treatment across all visits: 4 weeks (p=<0.05), 8 weeks (p=<0.05), and 12 weeks (p=<0.05).

The mean alterations in HR are outlined in Table 7, showcasing the changes in HR measurements among the study participants over the 12 weeks.

Table 7 : Mean HR of Study Participants at Each Visit From Baseline to Week 12

|

HR |

Patients |

Mean (bpm) |

SE |

P value |

|

Baseline |

63 |

83.31 |

1.43 |

NA |

|

Week 4 |

60 |

77.98 |

1.19 |

<0.05 |

|

Week 8 |

57 |

72.51 |

1.59 |

<0.05 |

|

Week 12 |

55 |

70.93 |

1.29 |

<0.05 |

Figure 3 depicts the mean HR recorded at each visit following cilnidipine treatment. The average mean HR significantly decreased at each visit over the 12 weeks of the study.

HR: heart rate; bpm: beats per minute

Figure 3: Mean HR Measurement at Each Visit with Cilnidipine Treatment

Adverse Events

Among the 63 patients, 9 (14.29%) reported experiencing mild adverse events, while the remaining 54 (85.71%) did not report any adverse events. Dizziness was reported by 3 (4.8%) patients, while 3 (4.8%) reported headaches, 2 (3.2%) experienced vomiting, and 1 (1.6%) reported flushing. Notably, no patients reported peripheral edema or rash.

DISCUSSION

The current study demonstrated a direct and statistically significant correlation between treatment with cilnidipine and reduction in SBP (p<0.05), DBP (p<0.05), and HR (p<0.05) at every visit over 12 weeks. Further, this study also underscored the safety profile of cilnidipine, with no documented cases of pedal edema or rash and minimal adverse effects.

Chakraborty et al. conducted a meta-analysis of randomized and non-randomized clinical trials assessing the effects of cilnidipine monotherapy or combination therapy on SBP and DBP over 48 weeks. The study analysis compared changes in SBP and DBP between cilnidipine and other CCBs, which showed that cilnidipine led to a notable decrease (p<0.05) in SBP and DBP at the end of treatment, mirroring the effects of other CCBs (p<0.05). Another study by Naik et al. reported significant reductions in SBP (17 ± 0.8 mmHg, p<0.001) and DBP (6.6 ± 0.5 mmHg, p<0.001) at 24 months, along with a reduction in urinary albumin excretion, reinforcing cilnidipine’s potential renoprotective effects. The findings of these studies corroborate our study results, which show that cilnidipine effectively reduced SBP (p<0.05) and DBP (p<0.05) in individuals with hypertension over 12 weeks.

In another study by Das et al., the efficacy of cilnidipine in managing essential hypertension and its impact on HR over 24 weeks was evaluated. Following the 24-week duration, patients administered with cilnidipine exhibited a notable decrease in HR (p=0.00). This outcome aligns with our study findings, where cilnidipine similarly demonstrated a

significant reduction in HR (p<0.05) among patients over 12 weeks.

Thus, the overall observed reductions in SBP, DBP, and HR among the patient cohorts in the studies conducted by Chakraborty et al. and Das et al., along with our study, suggest a promising benefit of cilnidipine in modulating cardiac function among individuals with hypertension.

Mohanty et al. conducted a comparative study to evaluate the safety and tolerability of amlodipine and cilnidipine in patients with hypertension. In a group of 78 patients with hypertension treated with cilnidipine over 12 months, the following adverse events were reported: headache was observed in 4 patients (5.13%), fatigue in 3 patients (3.85%), dizziness in 3 patients (3.85%), ankle edema in 2 patients (2.56%), flushing in 2 patients (2.56%), constipation in 2 patients (2.56%), and weight gain in 2 patients (2.56%). Our study findings align with those reported here, showing no pedal edema or rash and rare minimal adverse effects like dizziness, headache, flushing, and vomiting. This suggests that cilnidipine demonstrates a favorable safety profile characterized by minimal adverse effects, a majority of which are mild.

Our study limitations include a relatively small sample size, a short follow-up duration, the absence of a control group, and potential internal validity issues due to the absence of blinding. As an observational study, it is also susceptible to selection bias and confounding, limiting the generalizability of the findings. Future research with larger cohorts, longer observation periods, and a randomized controlled design are needed to validate our findings on cilnidipine’s efficacy, safety, and tolerability profile.

CONCLUSION

Our study and supporting literature suggest that cilnidipine demonstrates effectiveness in lowering SBP, DBP, and HR in patients with hypertension, with minimal adverse effects in patients of Hospital Point G (Mali) and at the Treichville University Hospital (Côte d'Ivoire). Notably, cilnidipine's favorable safety profile, including the absence of pedal edema or rash and the minimal occurrence of headache and dizziness, underscores its potential as a well-tolerated antihypertensive medication.

While findings suggest its potential effectiveness and safety, limitations such as a small sample size, short follow-up, absence of a control group, and susceptibility to bias must be considered as it might affect generalizability. Future randomized controlled trials with larger cohorts and longer observation periods are needed to strengthen these findings and provide more conclusive evidence on cilnidipine’s role in hypertension management.

Acknowledgment: The authors would like to thank the Spellbound Inc. team for their constant guidance and publication support.

Funding: The authors declare that no external funding was received for this study. The research was conducted with personal/institutional resources without financial support from any funding agency, organization, or sponsor.

Conflict of interest: The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest related to this manuscript.

|

|

|

REFERENCES |

|

1. Iqbal AM, Jamal SF. Essential hypertension. [Updated 2023 Jul 20]. StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK539859/. 2. Hypertension [Internet]. World Health Organization. [cited 2024 Mar 18]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/hypertension. Published March 16, 2023. Accessed Feb 17, 2025. 3. Basu S, Malik M, Anand T, Singh A. Hypertension control cascade and regional performance in India: A Repeated Cross-Sectional Analysis (2015-2021). Cureus. 2023 Feb 25;15(2):e35449. doi: 10.7759/cureus.35449. 4. Countries [Internet]. World Health Organization. [cited 2024 Mar 18]. Available from: https://www.afro.who.int/countries. Accessed April 2, 2024. 5. Ruilope LM, Schiffrin EL. Blood pressure control and benefits of antihypertensive therapy: does it make a difference which agents we use? Hypertension. 2001 Sep;38(3 Pt 2):537-542. doi: 10.1161/hy09t1.095760. 6. van der Linden EL, Agyemang C, van den Born BH. Hypertension control in sub-Saharan Africa: Clinical inertia is another elephant in the room. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2020 Jun;22(6):959-961. doi: 10.1111/jch.13874. 7. Tocci G, Battistoni A, Passerini J, et al. Calcium channel blockers and hypertension. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol Ther. 2015 Mar;20(2):121-130. doi: 10.1177/1074248414555403. 8. Brewster LM, Seedat YK. Why do hypertensive patients of African ancestry respond better to calcium blockers and diuretics than to ACE inhibitors and β-adrenergic blockers? A systematic review. BMC Med. 2013 May 30;11:141. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-11-141. 9. McKeever RG, Patel P, Hamilton RJ. Calcium Channel Blockers. [Updated 2024 Feb 22]. StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482473/. 10. Adake P, Somashekar HS, Mohammed Rafeeq PK, Umar D, Basheer B, Baroudi K. Comparison of amlodipine with cilnidipine on antihypertensive efficacy and incidence of pedal edema in mild to moderate hypertensive individuals: A prospective study. J Adv Pharm Technol Res. 2015;6(2):81-85. doi:10.4103/2231-4040.154543. 11. Bulsara KG, Patel P, Cassagnol M. Amlodipine. [Updated 2024 Apr 21]. StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK519508/. 12. Chakraborty RN, Langade D, More S, Revandkar V, Birla A. Efficacy of Cilnidipine (L/N-type calcium channel blocker) in treatment of hypertension: a meta-analysis of randomized and non-randomized controlled trials. Cureus. 2021 Nov;13(11):e19822. doi: 10.7759/cureus.19822. 13. Chandra KS, Ramesh G. The fourth-generation calcium channel blocker: cilnidipine. Indian Heart J. 2013 Dec;65(6):691-695. doi: 10.1016/j.ihj.2013.11.001. 14. da-Silva RF-, Alves JM. Overview of Phase IV Clinical Trials Targeting COVID-19: Status Report of Studies Registered on the ClinicalTrials.gov Platform. Curr Med [Internet]. 2022 Jan 31 [cited 2025 Feb 17]. Available from: https://mediterraneanjournals.com/index.php/cm/article/view/610. 15. Htoo PT, Stürmer T, Girman CJ, Ritchey ME. Chapter 14 - Unmeasured confounding with and without randomization. In: Girman CJ, Ritchey ME, eds. Pragmatic Randomized Clinical Trials. Academic Press; 2021:185-205. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-817663-4.00016-7. 16. Naik A, Dewan D, Metha KD. WCN25-4621 Cilnidipine – a novel CCB reduces blood pressure, heart rate, and proteinuria in Indian hypertensive patients. Kidney Int Rep. 2025;10(2 Suppl):S348. doi:10.1016/j.ekir.2024.11.644. 17. Das A, Kumar P, Kumari A, et al. Effects of Cilnidipine on Heart Rate and Uric Acid Metabolism in Patients with Essential Hypertension. Cardiol Res. 2016;7(5):167-172. doi:10.14740/cr494w. 18. Mohanty, M., Tripathy, K. P., Srakar, S., & Srivastava, V. Evaluation of safety and tolerability of amlodipine and cilnidipine - A comparative study. Sch J Appl Med Sci. 2016;4(8C):2884-2894. doi: 10.36347/sjams.2016.v04i08.032. |